Living microbes found deep inside 2-billion-year-old rock

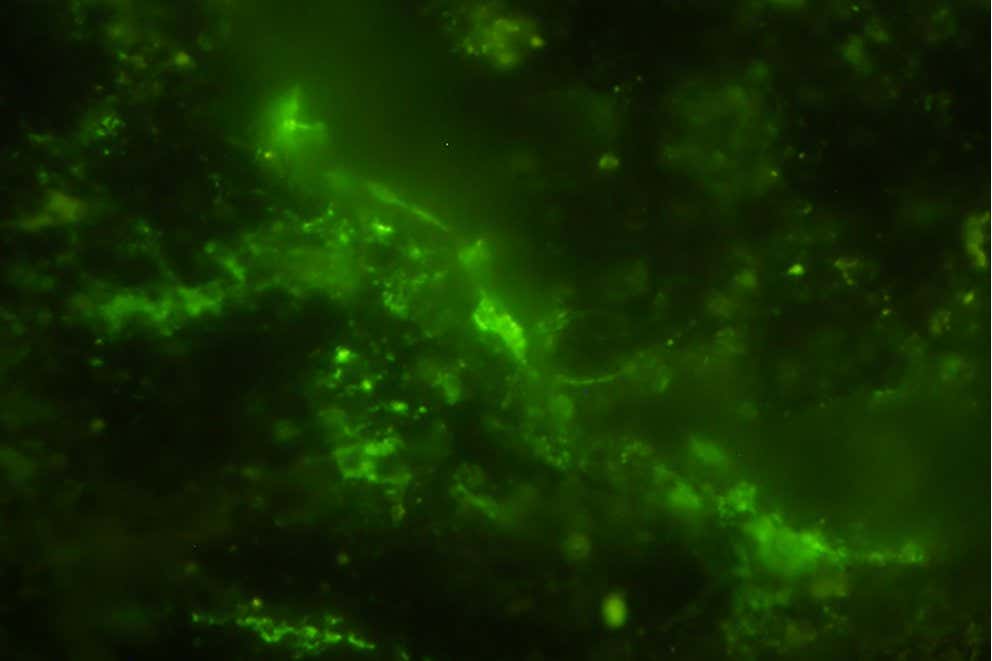

Cells found inside ancient rocks, their DNA stained with a green fluorescent dye

Y. Suzuki, S. J. Webb, M. Kouduka et al. 2024/ Microbial Ecology

Microorganisms have been found living in tiny cracks within a 2-billion-year-old rock in South Africa, making this the oldest known rock to host life. The discovery could offer new insights into the origins of life on Earth and may even guide the search for life beyond our planet.

We already knew that deep within Earth’s crust, far removed from sunlight, oxygen and food sources, billions of resilient microorganisms survive. Living in extreme isolation, these slow-growing microbes divide at a glacial pace, sometimes taking thousands or even millions of years to complete cell division.

Advertisement

“So far, the oldest rocks in which microbes have been found are 100-million-year-old seafloor sediments,” says Yohey Suzuki at the University of Tokyo. “We know it’s possible that microbes can grow using something in these ancient rocks.”

Now, Suzuki and his colleagues have pushed that record back by nearly 2 billion years. They obtained a 30-centimetre-long cylindrical rock core from 15 metres below the surface of the Bushveld Igneous Complex in north-eastern South Africa, a vast formation of volcanic rock that formed more than 2 billion years ago. When they sliced open the core, they discovered microbial cells living in the rock’s tiny fractures.

The team stained the microbes’ DNA and imaged them with a scanning electron microscope and fluorescent microscopy, then compared them to potential contaminants to confirm they were indigenous to the rock sample. They also noted that the cell walls of the microbes were still intact – a sign the cells were alive and active.

“Have you seen rocks from a volcano? Do you think anything can live in those rocks?” says Suzuki. “I certainly didn’t, so I was very excited when we found the microbes.”

The team thinks the microorganisms were carried into the rock via water shortly after its formation. Over time, the rock was clogged up by clay, which may have provided the necessary nutrients for the microorganisms to live on.

“The microbes in these deep rock formations are very primitive in evolutionary terms,” says Suzuki, who now hopes to extract and analyse their DNA to learn more about them. Understanding these ancient organisms could provide clues about what the earliest forms of life on Earth may have looked like and how life evolved over time.

This discovery may also have important implications for the search for life on other planets. “The rocks in the Bushveld Igneous Complex are very similar to Martian rocks, especially in terms of age,” says Suzuki, so it is possible that microorganisms could be persisting beneath the surface of Mars. He believes that applying the same technique to differentiate between contaminant and indigenous microbes in Martian rock samples could help detect life on the Red Planet.

“This study adds to the view that the deep subsurface is an important environment for microbial life,” says Manuel Reinhardt at the University of Göttingen, Germany. “But the microorganisms themselves are not 2 billion years old. They colonised the rocks after formation of cracks; the timing still needs to be investigated.”

Topics: